Sidney Lumet (1924-2011) started his film directorial career by famously exploring the peer pressure to do the wrong thing in a bad world in “12 Angry Men” (1957) and concludes it with “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” (2007), set in a laser-focused reality wherein you perhaps have to do bad things to get by.

Sometimes appearing on lists of Lumet’s 10 best films (no small feat, as he averaged nearly a film per year from 1957 through the end of the century), “Devil” is one of two notable screenplays from Kelly Masterson, the other being the grim, overrated “Snowpiercer” (2014). Maybe he’s one of those people who have one great script in them.

While helped by a stellar cast and a time-hopping device — where at key moments we go back to learn what led up to the moment for a supporting character from that scene – Masterson delivers a “Simple Plan”-style plot that holds your attention.

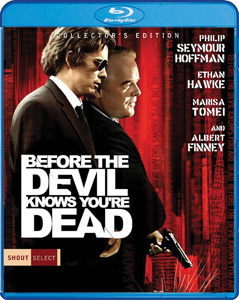

“Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” (2007)

Director: Sidney Lumet

Writer: Kelly Masterson

Stars: Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ethan Hawke, Albert Finney

Real-estate payroll manager Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and maintenance worker Hank (Ethan Hawke) are both struggling with money. Around the time of the housing bubble bursting, Andy appears to be doing OK, affording a nice vacation to Rio, a ritzy NYC apartment and an out-of-his-league trophy wife (Marisa Tomei).

Hank not so much; his apartment is rattier. Then again, he has his own place in NYC where the walls are more than an arm-span apart. At any rate, they go in on a get-rich-quick scheme to hit a suburban jewelry store. As more characters – a mother and father (Albert Finney); a high-class drug dealer; an amateur robber, his wife and the wife’s brother (Michael Shannon) – are introduced into the interconnected circle with fateful inevitability, the plan ain’t so simple anymore.

12 angry (or otherwise troubled) people

Although the plotting is smart and intricate, Masterson might be more interested in morality. The film’s core nugget of wisdom is delivered by one of the least ashamed bad guys, a veteran diamond fencer: “The world is an evil place. Some of us make money off that evil while it destroys others.”

The non-linear structure would seem to make plot paramount, but the rewound revelations also illuminate Andy’s and Hank’s life situations. “Devil” surprisingly becomes a story about a dicey brotherly bond, a fractured father-son relationship, and an imploded marriage where neither side admits to the situation.

The conclusion is powerful but leaves some threads dangling; this film might’ve benefited from a “Here’s what happened next” epilog, but it’s hard to not do those in a gaudy way.

Though actually a pretty smooth watch, “Devil” keeps a tight and serious focus. In order to take a step back to see a bigger picture, you’d have to pause the movie. How desperate was the brothers’ plight? How much of it was due to external forces and how much was it their own fault?

Though the full backstory is off-screen, it seems “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” isn’t a story of the world painting the brothers into a corner. They always had other options, and often chose a bad one. But they are sympathetic in the sense that they know the game – “make money off the evil world” – yet aren’t themselves evil enough to be elite players.