Naoki Urasawa writes and draws “Monster” (1995-2002) like a movie. I’m simply describing what a graphic novel is, but this manga master especially reminds us with the way he delivers performances, cinematography, pacing and mood.

Story-wise, this is straightforward stuff. (I’m reviewing Vol. 1 of the nine-volume Perfect Edition here; this comprises Volumes 1-2 of the original collections; the first 16 chapters of what eventually became 162 chapters.) Dr. Tenma, from Japan but working in Germany, is disillusioned with the office politics that interfere with him saving lives. The brain surgeon saves a kid’s life, disobeying his boss’s command to leave that patient and operate on the mayor.

Tenma’s shot at career advancement is over, and he mulls injustices to himself and others, wondering if he can carve out a path of morality in an immoral world. We feel like we’re “watching” a David Fincher movie. It’s not that Urasawa’s themes are at all fresh: “Monster” is like an encyclopedia of humanity’s injustices and absurdities, from the POV of someone not OK with playing the game. It’s that these issues are eye-opening and provocative to Tenma.

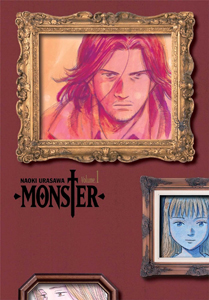

“Monster” (Perfect Edition Volume 1, 2014)

Collects chapters 1-16 (1995 in Japanese, 2006 in English)

Writer and artist: Naoki Urasawa

Genres: Crime, mystery, thriller

Setting: Mid-’80s to mid-’90s, Germany

Note to readers: The Book Club Book Report series features books I’m reading for my book club, Brilliant Bookworms.

Every character is a trope given realistic life by a “performance” of rich characterization via how Urasawa draws expressions, combined with traits we learn via dialog and behaviors. This can be as mundane as a newspaper editor whose colleague comments that he should bathe more often. As such, we know he rarely leaves the office.

A more colorful case is a German national investigator with an incredible memory. He mimics typing when interviewing people; this records information into his brain. The simplest trope is the hot young hanger-on who aims to make Tenma her husband until his career misstep; she immediately switches to Tenma’s replacement. But even she resists being a total cliché as things progress.

Allies, enemies and mysteries from all corners

Tenma tries to ally with the newspaper man because the cops reject his growing belief about unsolved serial murders of middle-aged, childless couples over the past decade (from the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s) in the uneasily reunited Germany. Tenma believes a boy, aged 10 to 20 during this period, is the killer. So this may be your standard incompetent cop work in a way, but it’s somewhat understandable. There simply aren’t serial-killer children.

The mostly black-and-white “Monster” unfolds slowly. If the art wasn’t so great, it would be too slow, like the majority of prestige TV series that try to mimic the elite ones. On the other hand, each chapter reads very fast. You’ll turn the pages quickly and not get tripped up too often by details, partly because Tenma often turns them over in his mind (a not-unwelcome artifact of the original serialized publication in Big Comic Original). Later, the amnesiac Nina/Anna – the brother of Johan, the boy Tenma operated on – reflects on her mysterious past through similar thought bubbles.

Being translated from Japanese into English (by Camellia Nieh), while set in Germany, “Monster” occasionally has jittery dialog flow. In this way, the simplicity of the story – or at least of each episode within the big, complex story – is a benefit. We spend most of our time enjoying the characters, although a mystery does gradually grow and encroach because Johan is the only suspect yet many things don’t snap into place. At one point, two murders happen simultaneously on different sides of a city.

“Monster” deepens as it goes along because Urasawa widens the scope. Any given new character is attached to more new characters, and so forth. There’s a serious danger it could get unwieldy, but it doesn’t happen in these first 16 chapters, because the author makes sure we’re always connected to Dr. Tenma or Anna.

Mulling manga

I don’t read a lot of manga (I had tackled the “Star Wars” movie adaptations, a good starting point since I already knew the tale), but my biggest worry was quashed almost immediately upon cracking “Monster” open. You read in exact reverse of the Western style; you go back to front, right to left, and right to left on each page as you go top to bottom. It easily becomes natural because of course the action and word bubbles flow that way.

Not once did I do it wrong, although I marvel at how the back cover is the front cover, and I wonder about shelving if I were to become a manga nerd; do you shelve right to left? At any rate, I’m definitely going to explore more manga and look into the rest of the “Monster” saga, of which I’ve covered a mere 11 percent so far. I can tell I’ve waded into the shallow waters of an epic masterpiece – definitely on the art side, and possibly on the story side too.