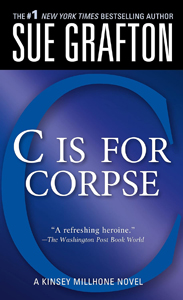

“C is for Corpse” (1986), appropriately, has the most Character of the Kinsey Millhone series up to this point. Kinsey becomes comfortable in her own skin, often bluntly asking sources or suspects the questions she needs answers to. This might partly be a case where Sue Grafton needs the information revealed to Kinsey and the reader, and she’s tired of tip-toeing around, but it’s also good personality creation.

In another angle on character creation, Kinsey has her most heartfelt friendship, with Bobby Callahan, a 23-year-old who has suffered brain damage in a car accident (which probably wasn’t an accident) and can’t remember who was trying to kill him or why. Grafton nicely portrays the way a memory-troubled brain knows that it can’t remember, something that applies to Bobby’s physical trauma but could also stand in for age-related memory loss and other conditions. This is not “just go with it” soap-opera amnesia but rather a challenging, life-altering condition.

Bobby’s teenage stepsister Kitty is also quite a piece of work, as Grafton paints a picture of someone so anorexic that she’s skeletal. This was slightly before mainstream knowledge of the disorder wherein someone declines to eat; in fact, Grafton uses “anoretic,” before anorexic became the accepted term.

“C is for Corpse” (1986)

Author: Sue Grafton

Series: Kinsey Millhone No. 3

Genre: Hardboiled mystery

Setting: 1982, Santa Teresa, Calif.

While Kinsey started in the Marlowe mold of not having any friends, it’s hard for an author to maintain that as a series inevitably becomes peppered with recurring characters. We check in with Kinsey’s cop almost-boyfriend from “B is for Burglar,” Jonah. And we get more of her warm connection with her octogenarian landlord, Henry, who it appears is being scammed by a new girlfriend. Since the Callahan case is slow to progress, she can take out some frustrations on this nasty woman who leaves an easier trail.

‘C’ is for (playing it) cool

“Corpse” is a weaker mystery than “A is for Alibi” and “B” but a better overall novel. Despite not being solvable until we get actual clues to work with, which doesn’t happen until the final act, it does give a strong portrayal of how the private detection game works. It’s about gathering information, and sometimes you are unable to gather the information you need.

While Kinsey can be blunt with some people, she can have a delicate touch at other times. Bobby’s friend who mans a bowling-alley counter is reluctant to talk, and Kinsey senses he knows something. She also senses that badgering him is not the right play, so she plays it cool.

Despite being well-organized – keeping notes on index cards – Kinsey is imperfect and OK with that. Her relatability is why we like her. In chapter 22, she pops in on a suspect/source:

I hadn’t really given a lot of thought to how I was going to handle this. Every time I rehearse these little playlets in advance, I’m brilliant and other characters say exactly what I want to hear. In reality, nobody gets it right, including me, so why worry about it before the fact?

‘C’ is for (a dearth of) clues

This novel has a great sense of place, first at the Callahan mansion where we meet Bobby’s family and friends (a.k.a. red herrings and misleads). After Bobby’s death (which Kinsey spoils for us on page one, as she always does with one key piece of information in her first-person “reports”), his mother says there’s no rush to change his bedroom into a sewing room, as the house has a dozen other unused rooms.

Even better is the auxiliary county medical center, the old building on the edge of town that was built in the 1920s. Because the new downtown building can’t fit everything, the old one is still used for paper record storage (transferring information from paper to new-fangled computers was not an overnight process in the Eighties). Also, some labs are still there, plus morgue overflow and some offices.

With words, Grafton crafts a liminal space, one of those old but clean buildings wherein 20 percent of it is in use and 80 percent isn’t. I picture 100 empty parking spaces even if all the employees were to be on shift. In addition to being a part-artifact, part-functioning element of a growing and morphing city, the annex is an evocative location for a final showdown, which happens to be of the “can’t put it down till I’m done” variety. In this way, the long holdout makes answers even more desirable.

Although “C is for Corpse” does not evenly spread out the clues, instead having everything come together thanks to a late revelation of a past event we were not privy to (something Agatha Christie sometimes did), it’s very enjoyable. Not all mysteries are fun puzzles; some are grunt work, peppered with fear, grief and frustration. The latter type can also be satisfying and entertaining, as Grafton proves.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.