The hydrogen-bomb war (or atomic, or nuclear – pick your poison) was a regular obsession of Philip K. Dick’s. Many of his contemporary-set stories find people worrying about a bomb that could fall at any moment, and many of his future stories are set in a post-bomb world.

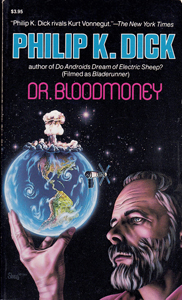

But “Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb” (written in 1963, published in 1965) is a rare novel where he shows the day of the bombings (Emergency Day, in the future of 1981) – presumably between the USA and the USSR — and the immediate aftermath.

Life after E-Day

“Dr. Bloodmoney” rings true in spirit, if not in detail, to what life would be like as society gradually rebuilds. Despite including E-Day itself and the Dickian staple of people with special powers courtesy of the radiation, this is a rather flat slice-of-life yarn focusing on a community in Marin County, north of the Bay Area, seven years after the exchange of bombs. While it’s imminently readable, there’s not much urgency in the narrative.

“Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb” (1965)

Author: Philip K. Dick

Composition year: 1963

Genre: Post-apocalyptic science fiction

Setting: Bay Area, the future of 1981

“Dr. Bloodmoney” does boast some chuckle-worthy Dickian mutants, though. My favorite is title character Dr. Bluthgeld’s dog, Terry. The dog can talk, barely, but still has a dog’s level of intelligence and interests. We almost feel bad for Terry as he works hard to bark/speak words such as “Whuuuuuut?” There’s also a rat that can play the nose-flute and cats that build little houses.

On the human side of the ledger, Dr. Bluthgeld – a former government scientist who blames himself for a 1972 bomb test in the atmosphere that results in the first wave of mutants – has a power wherein his worries inadvertently become reality.

That said, E Day isn’t specifically his fault. Although his name is perhaps a commentary on the military-industrial complex, where special interests get rich from perpetual war, Bluthgeld himself is alternately sympathetic and pathetic.

Phocomelus and homunculus

Also emerging from a massive cast of characters are a phocomelus and a homunculus. I know these two terms only from PKD works, but the web tells me they are real words. The latter, represented by Hoppy Harrington, is a man with stubby, useless limbs.

However, he gets by with a cart and mechanical extensors – plus telekinetic powers: He can move objects with his mind. As Hoppy’s powers grow, the Marin community depends on him for protection, and we get a lesson in the cure being as dangerous as the disease.

The homunculus – which simply means a small humanoid creature (I picture a baseball-sized clay-like being) – is Bill Keller, the twin brother of 7-year-old Edie Keller who lives in her abdomen. He can transfer into other beings if Edie gets in close contact with them. Although he and Edie get along well, he longs to exist as a distinct being and see the world.

As if that isn’t enough weirdness, this is also the novel where astronaut Walter Dangerfield – whose mission to Mars goes haywire on E-Day – is stuck circling the Earth in his ship. So he essentially becomes a radio DJ, engaged in a mutual attempt to stay sane by chatting with and playing music for the people below.

A spice of strangeness

“Dr. Bloodmoney” is peppered with Dickian strangeness, but only as a spice. The main dish is the process of rebuilding humanity after a devastating event. Stuart McConchie (who pre-bomb is a Bay Area TV salesman in the tradition of PKD’s realist novels) runs into frustrations such as his horse being killed and eaten when he parks it at an Oakland pier.

Andrew Gill is a successful entrepreneur, but his company rolls cigarettes by hand; automation – as proposed by McConchie — would enormously expand his enterprise.

The author and his characters approve of the rebuilding of society, but there’s some wariness peppered in, as if the hydrogen bomb is the direct end result of automated production of goods. I’m reminded of that classic montage in “Futurama” where Fry is filled in on the millennium he missed: Society builds up, is flattened by war — rinse and repeat.

Perhaps that’s why “Dr. Bloodmoney” is a bit unsatisfying. Dick doesn’t have an answer for how to stop humanity’s cycle of self-destruction, because it’s beyond any individual’s control. Bluthgeld thinks he’s responsible since he had a hand in the 1972 test, but he’s delusional – he’s not as bad as he thinks he is nor as good as he wants to be. Hoppy has superpowers, but only to destroy, not to speed up the rebuilding.

Bill Keller’s greatest achievement is to become a self-functioning person. But even then, he’s only one man.