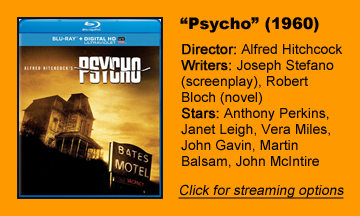

We all go a little mad sometimes, so from Nov. 27-Dec. 11 we’ll be dragging the swamp behind the Bates Motel for insight into the films of the “Psycho” franchise. First up is “Psycho” (1960):

3 shocking moments

“Psycho” has only three shocking moments: the shower scene, Arbogast’s murder and the reveal of Norma’s corpse in the fruit cellar. But although its dearth of big moments differs from modern horror films, it’s a masterpiece of slowly ratcheting tension before we even meet Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) a half-hour into the picture.

Similar to Jimmy Stewart driving all over town in “Vertigo” (1958), Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) drives off with $40K in stolen cash, and we feel her paranoia as she examines the rear-projected surroundings in her mirrors.

Director Alfred Hitchcock and cinematographer John L. Russell crop closely on Crane’s face as Leigh – whose daughter, future scream queen Jamie Lee Curtis, wasn’t yet 2 years old when “Psycho” premiered — does most of her acting through the set of her jaw and the voice-over thoughts in Marion’s head.

I imagine Bernard Herrmann’s tense earworm score is running through her mind too. Marion dreams up what people are saying about her behavior after encountering her, starting with a California Highway Patrol officer (Mort Mills) who finds her sleeping in her parked car. (And we’re reminded that it’s not a new thing by any means for people to feel harassed by law enforcement.)

The story of … Marion?

It’s remarkable how much time screenwriter Joseph Stefano spends on Marion – and how often Hitchcock lingers on the envelope of cash — considering that her thievery is not relevant to where the plot will eventually go. Marion swaps cars at a used-car lot on her drive from Phoenix to Fairvale, Calif., before stopping at the off-the-beaten-path Bates Motel on one of those rainy nights where you can’t see well enough to drive.

Robert Bloch’s “Psycho” novel from one year earlier spends much less time with Marion, instead opening with Bates and later focusing on the various investigators.

In “Psycho,” Hitchcock proves that viewers will sympathize with the focal character, regardless of what they’ve done. Some argue Marion’s murder in the shower marks the beginning of the slasher genre (or at least the beginning of its roots). Interestingly, many future shower scenes are played for fake-out scares and titillation rather than an actual killing.

Even though she’s a thief, Marion remains one of the most sympathetic shower-scene victims ever because of how the sequence shockingly interrupts her peace and privacy.

Norman grabs our attention

After that classic sequence, Norman has our attention. On this viewing, I imagined watching “Psycho” without knowing the outcome, and Stefano plays this as a whodunit with the heaviest suspicion laid on Norman’s mother (the voices of Virginia Gregg and Jeanette Nolan).

Norman initially gives an impression of being abused by his mother. But he’s also shifty and awkward when taking to Marion, so he’s not off the hook as a suspect. Regardless of whether he’s the killer or merely protecting his mom, on some level we want him to successfully cover up the murder.

“Bates Motel” (2013-17) would later build a whole series around us rooting for the bad guy because he’s psychologically troubled. And on this viewing, I gained a new appreciation for how Freddie Highmore’s performance and appearance are so close to Perkins.

When “Psycho’s” Norman stutters in response to the grilling from private investigator Arbogast (Martin Balsam), we cringe; when he behaves smoothly – like in the early moments of Marion’s boyfriend Sam (John Gavin) and sister Lila (Vera Miles) checking into the hotel – we feel proud of him.

Its only pacing problem

Once Lila discovers Norma’s corpse and Stefano and Hitchcock are done keeping the truth at arm’s length, “Psycho” ends with its only pacing problem: psychiatrist Richman (Simon Oakland, “Kolchak: The Night Stalker”) takes forever to explain to Marion’s loved ones and law enforcement the internal motivations behind Norman’s killings.

I almost expect Lila to stand up and say “We get it already!” (If you’re comparing the continuities of the films with “Bates Motel,” we get some background here: The films’ Norman killed his mother and her lover, plus two other girls, prior to “Psycho’s” events.)

Maybe psychological horror was at a more primitive age in 1960, and the doctor’s explanation is not only enlightening to that audience but also important for restoring their sense of structure and normalcy, which Hitchcock has steadily eroded.

Still, as the three sequels, the 1998 shot-for-shot remake and “Bates Motel” prove, Norman Bates still fascinates us as a template for aberrant and abhorrent behavior; he still keeps us off balance. And while “Psycho’s” killing of its main character is now a well-known novelty, it remains effective as a psychological trick.

Schedule of “Psycho” reviews:

Friday, Nov. 27: “Psycho” (1960)

Wednesday, Dec. 2: “Psycho II” (1983)

Friday, Dec. 4: “Psycho III” (1986)

Wednesday, Dec. 9: “Psycho IV: The Beginning” (1990)

Friday, Dec. 11: “Psycho” (1998)