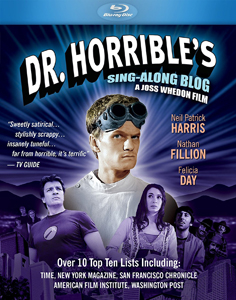

So I’ve finished my rewatches of all the Joss Whedon series between 1997-2010 except one – and it’s the most unusual one. “Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog” (2008) is three 15-minute web episodes that add up to length of one TV episode. It was penned by Whedon and his brothers Zack and Jed and Jed’s wife Maurissa Tancharoen (who also plays Captain Hammer Groupie No. 1) during the TV writers’ strike.

It’s not the first web show by any means – Felicia Day, who plays love interest Penny, launched “The Guild” a year earlier. But 2008 was a breakout year for web series (I had four of them in my top 10 TV list), and the massive number of clicks “Dr. Horrible’s” received made it clear to the industry that TV shows could be made outside of networks. It’s not a stretch to say “Dr. Horrible’s” success played at least a small part in the fact that we have streaming services today.

It’s also unusual in that it’s the only pure comedy installment in Whedon’s oeuvre. Usually, he likes drama and comedy all tangled up together so even a seasoned audience is taken off guard by both laugh-out-loud humor and cry-into-a-towel tragedy. But “Dr. Horrible” is intentional schmaltz. It mostly works on that level, and it gets a lot of goodwill from the fact that it could be watched for free online (the DVD costs extra).

“Dr. Horrible” is horribly overrated, though. It’s inherently ridiculous to compare 45 minutes with entire series, but it’s silly that “Dr. Horrible” ranks second among Whedon’s five works from 1997-2010 on the IMDb ratings, with its 8.7 coming in second only to “Firefly’s” 9.1. It obviously falls short of an average episode of “Buffy” (8.2), “Angel” (8.0) and “Dollhouse” (7.8).

The songs aren’t as memorable as those in “Once More With Feeling,” which Whedon wrote in the summer between Seasons 5 and 6 of “Buffy.” Although Whedon says on the commentary that he thought of the “Dr. Horrible” concept a year before production began, the songs are obviously a bit more cranked-out and silly.

The jokes mostly land. “The hammer is my penis” is a masterpiece of blunt humor, even though – no, BECAUSE – we can see it coming from a mile away. On my first viewing, when the camera held on Dr. Horrible (Neil Patrick Harris) a beat too long, I knew Captain Hammer (Nathan Fillion) was going to return to the frame and say something like that. That made me feel like I was an insider — on the Whedon wavelength.

Other jokes land flat for me, such as the idea of Bad Horse, “the Thoroughbred of Sin,” being an actual horse. But, certainly, it’s never boring. At 45 minutes, with songs and silly action scenes and a love triangle, it holds your attention and leaves you with a permanent smile.

The premise is appealingly offbeat, too: As the title and logo suggest, this is the villain’s perspective in a comic-book superhero’s world. The opening scene is a vlog entry from Dr. Horrible updating his fans (and viewers) on how his maniacal laugh and transmatter ray are coming along: good on the former, not-so-good on the latter – a bag of gold bars from the bank vault looks like a bag of cumin (the prop probably was exactly that, leading to the in-joke of Horrible saying the ground-up gold bars smell like cumin).

The problem with “Dr. Horrible” is that it’s hard to tell what message the show is sending. It might be unfair to hold a short comedy cranked out during the writers’ strike to high standards, but Whedon fans are conditioned to find the meaning in his works.

Is it a parody of the superhero genre – or perhaps even a critique of the genre’s potential for shallowness? Whedon grew up loving “X-Men” comics, and he had used the genre’s foundation in his previous series. He flipped the traditional script by having Buffy be a superhero rather than a victim, as blonde teenage girls usually had been portrayed. “Angel” was often like “Batman,” and “Firefly” – although not in the superhero genre — had Big Damn Heroes. Despite often flipping clichés on their heads, these worlds featured clear Goods and Evils.

In “Dr. Horrible,” the villain (Horrible) and hero (Hammer) occupy those traditional roles among the populace and opinion leaders (newscasters played by “Buffy” scribes Doug Petrie and Marti Noxon sing Hammer’s praises). They both label themselves thusly – Horrible is open about his intention to join the Evil League of Evil, and in “Everyone’s a Hero,” Hammer notes that while everyone can be a hero, for most people other than him, it will be in a “not-that-heroic way.”

But in many ways, Horrible is the hero. A viewer (unless you are heartless) immediately feels sympathy for Horrible because he loves fellow laundromat patron Penny from afar but can’t work up the nerve to talk to her. By contrast, Hammer is an a**h***. He dates and beds Penny precisely because Horrible is interested in her. When Penny is hurt and dying, Horrible goes to her side; Hammer runs off because he has a boo-boo – he clearly doesn’t care about her fate.

Horrible befriends Moist (Simon Helberg), his mild-mannered roommate who has a sweating problem, whereas Hammer is too narcissistic to have friends. He can land any woman he wants, but he discards them after one night; he’s considering having sex with Penny a second time mainly to stick it to his rival and because “They say you get to do the weird stuff.”

Until the final scene, Horrible had never killed anyone. He turns down a challenge to fight in a park because there would be kids there. His main weapon is a freeze ray, which isn’t even like Mr. Freeze’s gun, it just freezes a person in time for a while. To be fair, Hammer possibly hadn’t killed anyone, either.

In that final scene, Horrible – having changed the freeze ray into a death ray — intends to kill Hammer, but he hesitates. When Hammer gets hold of the weapon, he immediately shoots at Horrible. Only because the weapon is faulty does Horrible survive. Penny is killed by flying shrapnel. Who is to blame for that? I’d argue Hammer more so than Horrible, although there’s blame to go around.

It’s worth going off on a tangent here to look at Whedon’s political and societal views. From interviews he has given, we can infer that believes in the systemic status quo of “Dr. Horrible” (although not necessarily the people running the system), or at least that the status quo is inevitable (Horrible thinks the problems are rooted in “society”; he doesn’t use the word “government”), or at least that a minarchist or anarchist society would be worse (such a perspective is not offered on this show).

In “Serenity: The Official Visual Companion,” he takes pains to note that he’s not a libertarian:

“(Mal is) everything that my hero is not, because he’s somewhat of a reactionary, he’s a conservative kind of libertarian guy. I’ve often said that if Mal and I sat down to dinner, we’d have a terrible time. I don’t actually agree with most of what he says.”

Whedon goes on to equate Inara with “everything that’s good about (the Alliance) — enlightenment, education, self-possession, feminism.” (This isn’t to say that Whedon wrote the Alliance as heroes and the Serenity crew as villains. He did not. It’s just that his personal views aren’t libertarian, whereas “Firefly’s” message leans in that direction. A similar contradiction can be seen in “Dollhouse” and Season 4 of “Buffy.”)

The socio-political crux of “Dr. Horrible” finds Penny gathering signatures to turn a city-owned building into a homeless shelter. If Whedon is stuck on the notion that certain good things can only come from centralized government, he probably wouldn’t entertain the notion that the city government caused a homeless problem in the first place (or if it did, that the homelessness problem outweighs the good things government does), but he almost certainly would say government has a duty to try to fix it.

So that’s where the script flips: Horrible is more interested in fixing this problem than the disengaged Hammer is. Horrible signs the petition and tells Penny she’s treating the symptom, not the problem; she agrees with him, but doesn’t know of a solution. Representing the status quo, Hammer provides the key signature to get the homeless shelter approved, but obviously he’s doing it only to impress Penny and antagonize Horrible.

Representing potential revolution, Horrible wants a new status quo – because “the status is not quo.” However, Horrible’s solution is not to get government out of the way, his view is similar to the socialist mantra of “getting the right people to run things.” On his vlog, he says, “The world is a mess and I just need to rule it.” To Penny, he explains further: “I’m talking about an overhaul of the system. Putting power in … different … hands.” Although Whedon says he’s not a libertarian, he also has never said he’s a socialist. And it would be dishonest to overlook the fact that Horrible is an outright criminal, too: He attempts to steal gold bars in the opening scene and does steal bags of money in the final scene.

Whedon’s theme might be that people battling for power and prestige – whether superheroes or supervillains – can both be threats to the common citizen (see Penny getting caught in the crossfire).

Or possibly, he might be saying that it’s all meaningless, making this the lone nihilistic show from a man who usually espouses existentialism. When Dr. Horrible wins – and thus becomes sort of a Darth Vader figure where he goes through the evil motions, with nothing else to live for after Penny’s death – there’s no sign that the city has changed. We don’t know if the homeless shelter is up and running, but clearly, the city hasn’t become a dystopian apocalypse with Horrible’s rule. In the final scene, everyone – not just Evil League of Evil members — is having a good time at the bar.

Further showing that the status quo is the real winner, none of the characters have grown. Arguably, they have in fact regressed: Horrible rules for his own sake; Hammer is getting psychological treatment, having experienced pain for the first time (this is contradicted in the Dark Horse one-shot comic by Zack Whedon, but whatever); and Penny chooses brawn over brains right up until her dying breath, even with Horrible being the one at her side.

Because of the lack of a clear theme and the characters’ regressive arcs, “Dr. Horrible” doesn’t transcend its base of fun humor and shouldn’t be lauded on the same level as Whedon’s legendary TV works. But nor should it be dismissed. It’s cute. Sort of a quiet, nerdy thing. Not my usual, but nice.