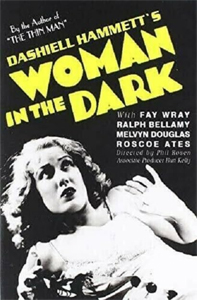

Watching “Woman in the Dark” (1934), it’s apparent why – other than classics like “The Maltese Falcon” (1941) and the “Thin Man” series – Dashiell Hammett adaptations aren’t talked about much. The filmmakers turn an engaging novella from 1933 – published in three parts in Liberty magazine – into a barely watchable film.

Granted, the version I saw had the music score blotted out, probably for copyright reasons. A good score might’ve made it much better, as the chemistry between Ralph Bellamy (as proto-“Cool Hand Luke” John Bradley, changed from Brazil in the novella) and Fay Wray (a year after “King Kong,” as Louise Loring) is good in that old-romantic way of a gruff protagonist and an endangered but fiery lady.

Before noir

Scholars say film noir started with 1941’s “Falcon,” and indeed – despite having some bad weather and dim lighting – “Woman in the Dark” stops short of full film noir. Director Phil Rosen operates more in the “gangster movie” tradition, or “proto-noir.”

“Woman in the Dark” (1934 movie)

Also known as “Woman in the Shadows”

Director: Phil Rosen

Writers: Sada Cowan (screenplay), Dashiell Hammett (novella)

Stars: Fay Wray, Ralph Bellamy, Melvyn Douglas

“Woman in the Dark” (1933 novella)

Author: Dashiell Hammett

Genre: Hardboiled crime/romance

Setting: 1933, rural area and city

The supporting cast is hit-and-miss, with Nell O’Day (as Helen, crazy for John but he thinks of her as a kid) among the hits and Melvyn Douglas (miscast as villain Robson) among the misses. But the big problems are Sada Cowen’s screenplay and the pacing.

It’s good that Cowen keeps Hammett’s story and most of the dialog (something that can’t be said for 1930’s “Roadhouse Nights,” a project birthed from “Red Harvest” that morphed into something different). But in order to achieve a 68-minute movie from a 76-page novella, she adds cliched scenes. For instance, John tells Louise all women’s middle names are “Trouble.” Hammett wouldn’t stoop to that level of hoary on his worst day.

Cowen also adds comedy via John’s fellow ex-jailbird friend Tommy (Roscoe Ates), who is put upon by his domineering wife and who makes dad jokes. (Admittedly a pretty good one: “I know a guy who shaves 40 times a day. … A barber.”

Though not celebrated as being among Hammett’s best, “Woman in the Dark” is not obscure. It was reprinted in paperback in the 1950s and in a classy hardcover in 1988, wherein novelist Robert B. Parker provides an insightful introduction, arguing that Hammett is trying to blend hardboiled with romance. It then got wider publication in the key Hammett collection “Crime Writings and Other Stories” (2001).

Crime and romance don’t mix … or do they?

I agree with Parker; Hammett struggles with the genres’ contradictions till the final page. But since John/Brazil – trying to keep a handle on his emotions, since a bout of rage had sent him to prison — is going through this struggle, too, “Woman in the Dark” plays out naturally. Despite good romantic leads, the film doesn’t approach what Hitchcock would do with the “man on the run, and the woman who might love him” subgenre in “The 39 Steps” (1935) and “Young and Innocent” (1937).

(SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

A weak point of the novella is that Hammett doesn’t have a revelatory statement to make. By the final page, and the final shot of the movie, we’re down to the rom-com manner of John/Brazil and Louise seeing past a misunderstanding and starting their “happily ever after” as we reach The End.

Hammett (and the movie) also closes with a sensible plot twist/explanation wherein it turns out the man whose head injury might send John/Brazil back to prison was actually further beaten up by the villain Robson. So we might not have realized we were reading a mystery, but we technically were. It’s not what you’d call a rousing conclusion, but …

(END OF SPOILERS.)

… the pleasure of reading Hammett’s prose and dialog exchanges is enough to make this an enjoyable novella. As with even the elite Hammett adaptations, but more so, the film version of “Woman in the Dark” can’t capture the rhythms, even if the words are identical. I have a theory that although Hammett originated hardboiled dialog in the 1920s, actors generally didn’t know how to say the lines until the 1940s.

“Woman in the Dark” is one of only four Hammett short-story adaptations, even with a generous accounting (the others are “Another Thin Man,” which recycles “The Farewell Murder”; the “Fallen Angels” TV adaptation of “Fly Paper”; and “No Good Deed,” which uses “The House on Turk Street”). So what the 1934 film lacks in entertainment value it gains in history-homework value.

Novella: 3.5 stars

Movie: 1.5 stars

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.