Travis McGee is John D. MacDonald’s continuation of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe in the timeline of knights-errant transposed into 20th century American crime detection, and “The Quick Red Fox” (1964) is his buttery-smooth answer to “The Little Sister” (1949).

Stunted stardom

This light 204-pager, the fourth McGee novel, is an intermittently heavy study of how Hollywood shapes people’s personalities and values – especially if they get into acting when young. The phenomenon is still present today, when we see a star interviewed and realize two things: 1, they are a skilled actor, because they are nothing like their characters, and 2, they are isolated from the main flow of society, stunted in emotions, knowledge and perspective.

The manifestation here is title (though not prominent) character Lysa Dean, a 33-year-old movie star who hires McGee – who lives on a houseboat in Florida – to learn who sent incriminating photos to her that could ruin her career (“cancellation” was a thing before recent years, even if not named as such). Dean has paid off the blackmail, but because the long-lens photos are of an outdoor patio orgy, any of another half-dozen people could be the main target or the perpetrator.

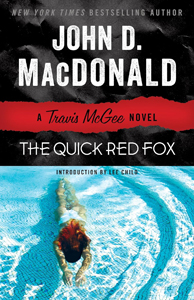

“The Quick Red Fox” (1964)

Author: John D. MacDonald

Series: Travis McGee No. 4

Genre: Hardboiled mystery

Settings: Florida, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Upstate New York, 1964

MacDonald moves between the advancement of the mystery and the romance – Travis gradually thaws Dean’s efficient assistant Dana – and short essay-like segments on moral and societal issues. In these segments, McGee channels MacDonald, who sometimes is a sharp analyst, like when he pontificates about the manner in which San Francisco went from a great city to an imitation of a great city (reflections that have become hyper-relevant since 1964).

At other times, McGee – although he doesn’t realize he has switched from analyst to pundit – universalizes his own morals. Notably, the moral wrongness of the weeks-long orgy hangs over “The Quick Red Fox.” This isn’t strictly because Dean feels dehumanized by the orgy. It’s because McGee – the first-person narrator – believes that Dean feels dehumanized by it.

Granted, McGee is not necessarily wrong; in fact, he is likely making the correct guess. It’s just that we don’t actually get into Dean’s head to know for sure what she’s feeling. MacDonald’s moral biases also show up when McGee tracks down Whippy, another one of the women in the sexually explicit blackmail photos. After being dominated by men, Whippy is now dominated by what MacDonald portrays as a cult of lesbians in a trailer park. After interviewing Whippy, McGee has to fight his way through them back to his car.

Pointing a long lens at morality

While this mild homophobia of McGee’s wouldn’t fly in modern times, and while he’s slightly less rigid with his moral code than Marlowe, he supplies the same appeal to a reader that Marlowe does. He’ll always do the right thing, and if he has to do a wrong thing – beating up a witness (who isn’t a good guy, granted, but also is not violent) for the sake of getting key information – he’ll do it if it means he gets a step closer to the right thing.

It’s important to Dana that Travis feels bad about doing that wrong thing. She flat-out says that’s what attracts her to him (which is necessary, since we only get Travis’ POV). In this book, McGee wraps up a relationship with a woman temporarily staying on his houseboat, has the love story with Dana, and fends off the advances of three damaged women.

In that sense, he’s James Bond (or the Bogart version of Marlowe), except that he’s noble and suspicious of women (rightly so, percentage-wise). He’s a consistent character, even if his easy ability to attract women isn’t likely outside the bounds of fiction. (But that’s the hardboiled genre for ya.) He’s mildly uneasy about his nobility, but has mostly settled into it despite being a bit short of middle-aged.

“Quick Red Fox” stumbles at the end, ultimately contriving convenient developments (both in putting a bow on the Travis-Dana relationship, and in wrapping up the case), so much so that one could argue Karma is another key character. The bad guys get what’s coming to them as assuredly as if hardboiled novels had to answer to cinema’s Hays Code.

Which isn’t to say this is a Pollyanna novel; McGee does not necessarily come out ahead except on the moral plane of catching a killer, and the gray-area characters don’t necessarily pay a price. “The Quick Red Fox” exists in a slightly softer hardboiled world, one where morality isn’t quite absurd. McGee is allowed to maintain his dignity a tad more than Marlowe.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.