Watched today, “Solaris” (1972) requires a pact with the viewer beforehand. It offers none of the things we look for in modern space films, such as action, fast pacing, colorful rogues and cool technology. I’m going to defend the film – which doesn’t put me in rare company, as it’s an acknowledged classic – but even I don’t know why the setup to psychologist Kris Kelvin’s (Donatas Banionis) information-gathering mission takes so long. On the whole, “Solaris” is as long as an “Avengers” epic, and much less stuff happens.

Wallowing, but also wonder

I’m familiar with the stereotype of depressive Russian cinema from Woody Allen’s “Love and Death” (1975), and – while “Solaris” is not shallow, and not as wallowing as it seems at first glance – it certainly fits into that stereotype. Four years earlier, “2001” was the definitive hopeful take on the Big Questions that might be answered via space exploration, and director Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Solaris” is the definitive downbeat take (even with several real-world moon missions having been completed by this time).

Oddly, though, “Solaris” does have a sense of wonder. Rooted in the screenplay by the director and Fridrikh Gorenshteyn, working from Polish author Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 novel, the sense of wonder and imagination goes to darker, but no less fascinating, places.

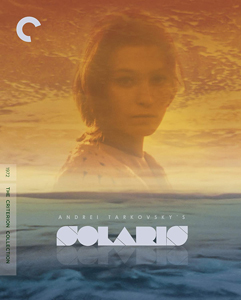

“Solaris” (1972)

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Writers: Fridrikh Gorensheteyn, Andrei Tarkovsky (screenplay); Stanislaw Lem (novel)

Stars: Natalya Bondarchuk, Donatas Banionis, Juri Jarvet

Instead of a monolith, here we have the water planet Solaris, which perhaps offers up the Secrets of the Universe, the Meaning of Life … you know, stuff that’s of interest to unhappy people. A cosmonaut from the previous Solaris mission, Berton (Vladislav Dvorzhetskiy), is so benumbed by his experience that for an endless interlude he stares ahead as his automatic car smoothly weaves through big-city traffic.

Finally, stuff happens

Does the setup before Kris’ mission need to be an hour long? Perhaps not, but that’s what modern remakes are for; see the 2002 version starring George Clooney. The intrigue kicks into gear when Kris – after meeting the curmudgeonly Snaut (Juri Jarvet) and the rude Sartorius (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), the other two Solaris staffers – catches glimpses of a young woman scampering around the circular-tubed station.

Tarkovsky stages these glimpses like the playful prologue to horror-film frights, but this is a think piece, not a scare piece. If you’ve signed that pre-film pact, “Solaris” doesn’t wallow, it mesmerizes. Interspersed shots of otherworldly waves and long looks at the trashed space station (people have gone crazy there before; Kris is merely the latest) are paired with Eduard Artemyev’s church music that’s one notch away from a funeral dirge.

But more often, the soundtrack consists of plain ole dead silence. I think some pretty, melancholy music might’ve helped the film along, but even in the state Tarkovsky leaves it in, it washes over a viewer. For the film’s first half, to expect “Solaris” to entertain you is like expecting an art gallery painting to entertain you.

Deep but tragic love

But the film develops thematic heft when Kris finds out the scampering woman is Khari (Natalya Bondarchuk), his wife who killed herself a decade ago after an argument with him. She’s an apparition from Kris’ mind, like what we’d later find in “Sphere” (1998), the Michael Crichton adaptation that was criticized for being a lesser “Solaris.” I’m an apologist for that film – which stylistically is wildly different from this one – but I have to admit “Solaris” boasts an extra level: It’s not just about Kris losing his marbles; we get to know the apparition as a person, too.

Banionis and Bondarchuk portray a deep but tragic love. Kris realizes Khari only exists on this drab space station or the waterlogged planet, and Khari grapples with her very identity and a desire to repeat her suicide. The film is thick with metaphors: We’re shown one of Khari’s resurrections, and it’s not exactly a happy, Biblical-style revival.

Tarkovsky and Gorenshteyn smartly intersperse Khari’s weird science-fiction question of “Who the hell am I?” with Kris’ – and viewers’ – question of “What is reality?” and fascinating sub-questions such as “What do we gain from seeking Big Answers?”

“Solaris” isn’t exactly a talky film, since long stretches go by without anyone speaking, but it’s in the conversations between Kris and Khari – and sometimes Kris and Snaut, and sometimes Kris and himself — that it gains depth and feeling.

Menacing emptiness

The junky space station where three socially challenged, middle-aged men are the only for-sure living beings is such a depressing place that any philosophical query raised there has as much menace as it does wonder. (The proportions are different when the “2001” astronaut taps into the monolith’s secrets, and the music cues set a different mood.)

Interestingly, Solaris and the station aren’t a trap; there’s no need to “escape” the setting like in the closing act of “Sphere.” Although generally classified as smart SF, “Solaris” isn’t interested in scientific laws like time dilation or the speed of light: Kris can go back to Earth if and when he wants, just as Berton did. It’s Solaris’ nature as a forbidden, foreboding frontier of knowledge — not its ill-defined distance from home — that makes it the edge of the universe.

That’s perhaps a flaw; maybe the planet should seem more inaccessible, more removed from the world Kris knows; maybe time-dilation should exist here. But actually, that quirk highlights Tarkovsky’s skill more. “Solaris” transports us to another place in the galaxy and has us thinking new thoughts.

I’d have to know someone is endlessly patient, and maybe a little bit depressive, to recommend this slow-burn epic. But it has come by its classic status honestly.