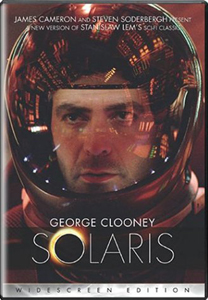

Writer-director Steven Soderbergh’s “Solaris” (2002) tries to do something different 30 years after the classic Russian adaptation of the Stanislaw Lem novel. It fails in a one-to-one comparison with the 1972 film on most counts. While it might seem to be to its credit that it tries a fresh take, that effort is never quite enough – even with A-lister George Clooney and the beautiful Natascha McElhone playing out the tragic sci-fi love story.

More meandering than meditative

Unfortunately, the notion of a reshoot of the same screenplay is a non-starters in Hollywood ever since Gus Van Sant destroyed his reputation by trying it, but in my opinion, that’s what a new “Solaris” should’ve been. Change the language to English, thus making the relationships clearer; update the sets and special effects; and tighten the first act and the more indulgent scenes a tad.

Soderbergh definitely embraces the “tightening” idea as his “Solaris” is an hour shorter than Andrei Tarkovsky’s. Lost is the meditative vibe, although oddly, the slowness is still there and this version somehow seems just as long as the classic version.

“Solaris” (2002)

Director: Steven Soderbergh

Writers: Steven Soderbergh (screenplay), Stanislaw Lem (novel)

Stars: George Clooney, Natascha McElhone, Viola Davis

I noted in my review of Tarkovsky’s “Solaris” that “Sphere” (1998) doesn’t get into the apparitions’ minds at all, whereas “Solaris” is interested in what apparition Khari is thinking.

Soderbergh’s “Solaris” goes a step further, making Rheya (McElhone) into a main character from the start. The central narrative is the tragedy in the relationship between Chris (Clooney) and Rheya. More on why that’s less interesting after the spoiler warning below.

Appealing design

First, the good things: I like the slick spaceship and space station — even if they look like most SF sets of the early Aughts — and the blue and green color palette, and the tendency toward dark lighting.

I like the pink-and-red planet Solaris (here, we see it from orbit, rather than from right above the weirdly roiling ocean), and the moody music by Cliff Martinez. There’ no question Soderbergh’s film is trying.

As a think-piece, though, it’s amateurish. The ’72 “Solaris” intriguingly asks whether the Big Questions are worth asking (because the answers might be a terrifying void of nothingness).

The ’02 “Solaris” spews out most of its philosophizing in a banal dinner conversation where psychiatrist Chris and his pals are on one side – arguing against God’s existence — and Rheya (whose job is undefined, but who I guess is a theist of some kind) is on the other.

Solaris’ effect on the people (Spoilers)

I’ll put a SPOILER WARNING here in order to discuss the characters further.

The tragedy of a relationship that has happy moments but ultimately fails is at the center of “Solaris” ’72. Khris decides to give up on that relationship after a few frustrating repeats of the cycle on the space station, and his bittersweet-ever-after false future is not one with Khari, but rather an opportunity to repair his relationship with his dad.

In “Solaris” ’02, Chris enjoys pseudo-intellectual dinner parties and Rheya does not (the first crack in their bond), and later, the big rift happens: She has an abortion because she assumes he doesn’t want kids – thus leading him to dump her and storm out. She then commits suicide and he feels guilty as hell.

This is a screen-written type of failed relationship rather than the more heartfelt and likely one of Khris-and-Khari. Even with Clooney and McElhone looking beautifully sad, enhanced by lighting and music to that effect, the utterly typical melodrama of their story is blatant.

What’s more, McElhone plays Rheya as a cipher even in the flashbacks, not just when she’s an apparition. “Solaris” ’02 doesn’t even hint at this in the narrative, but McElhone’s performance makes me wonder if a story where Chris always imagined her might’ve been more interesting.

While both versions leave unanswered questions, they are more naturally part of Tarkovsky’s film, more stiffly applied by Soderbergh. The former is an artist, the latter is a detail-oriented storyteller (see “Contagion”).

His decision to give more detail to the husband-wife relationship hurts the vibe, and his decisions of what to leave out of the other people’s stories feel random.

Among the two other space-station scientists, soft-spoken Snow (Jeremy Davies, in a warmup for his “Lost” role as Faraday) turns out to be the doppelganger of the real Snow, and we never learn the identity of Gordon’s (Viola Davis) Visitor.

Admittedly, it’s interesting in the abstract to think that Snow dreams of himself, thus causing Solaris to create a duplicate. But the film has little to say about this; it’s more of a “what the hell” revelation, and if this is truly a cerebral piece of SF, it should have more to say.

I admit my enjoyment of “Solaris” ’02 was hampered by having watched “Solaris” ’72 just prior; someone coming to this material fresh might get caught up in the mysterious nature of the premise.

Taking a modern, English-language crack at Lem’s novel isn’t automatically a bad idea. It’s just not in Soderbergh’s wheelhouse.