“Double Indemnity” (1944), one of the most well-respected and influential film noirs, is a near-masterwork of plotting regardless of genre. It can be enjoyed as a howcatchem, a “how are they gonna get away with it,” and a study of the infeasibility of trying to get away with a “perfect” murder – due to random bad luck or karma or paranoia or manipulation by a smarter game-player. Or all of the above.

Anyone who’s ever watched a movie can see the influence of “Double Indemnity.” For instance, the rhythms of Frank Drebin’s voiceovers and the way he talks to people and looks around surreptitiously in “The Naked Gun” could come straight from this movie. If I learned Leslie Nielsen studied Fred MacMurray’s turn as insurance salesman Walter Neff, I wouldn’t be surprised; but likewise, I wouldn’t be surprised if the hardboiled style simply soaked into many actors’ skill sets through the decades.

Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson is a definitive femme fatale, as her beauty and (totally misleading) sense of innocence draw Neff like a magnet. Neff is different from a typical hardboiled leading man, though. (For that title, I’d point to Bogart in “The Maltese Falcon.”)

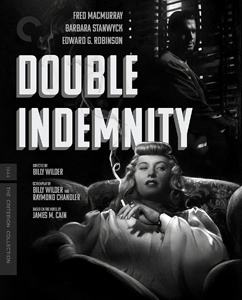

“Double Indemnity” (1944)

Director: Billy Wilder

Writers: Billy Wilder, Raymond Chandler (screenplay); James M. Cain (novel)

Stars: Fred MacMurray, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward G. Robinson

Many viewers will like Neff early on thanks to MacMurray’s suaveness and great lines like “Two F’s, like in Philadelphia.” The humorous lines are Wilder-esque for sure, but hardboiled legend Raymond Chandler co-writes, working from James M. Cain’s 1936 novel. However, Neff is not the sleuth here; that’s his boss, Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson).

(SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

What we’re actually seeing is Neff gradually fall under the sway of Phyllis, who is savvier than we initially realize. Later existential crime thrillers like “Fargo” and “A Simple Plan” would focus more on the idea that the world will balance the scales (in ironic fashion) if you do something wrong, and there’s some of that in “Double Indemnity” if you look at Neff and Phyllis as a team.

A not-so-simple plan (Spoilers)

If you look at it from Neff’s POV, the story is arguably one of female manipulation. But then things don’t work out well for Phyllis either – although there’s something to be said for the smoothness of what’s not so much her simple plan but rather her sociopathic life plan. Neff and we are hit with more horrifying knowledge: Phyllis killed her current husband’s first wife several years earlier, in order to marry him. Now that her marriage has soured, she’s carrying out her next money-making scheme.

Movies that map out intricate plotting by a character run into a potential issue: If the film itself has a logic hole, it can collapse – an ironic parallel to what the characters experience. Does “Double Indemnity” trip over its own feet? A case could be made that it does.

Neff kills Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers) by strangling him in the car ride to the train station. (Wilder artfully chooses to focus on Phyllis’ face as she drives while Neff carries out the deed.) Although this is never mentioned in the film, it’s common sense that the coroner would determine strangulation to be the cause of death.

Instead, Wilder and Chandler’s “howcatchem” element focuses on the gut instinct of Keyes, a master investigator of wrongful insurance claims. Keyes’ instincts lead him down the right path, and this provides much of “Double Indemnity’s” tension if we admit we want Neff to get away with it (within the film’s thrill ride).

My judgment is that “Double Indemnity” barely gets away with this bit of illogic because it’s so well plotted and well made in every other aspect. When trying to get away with murder, one mistake will trip you up. But …

(END OF SPOILERS.)

Wilder closes the sale

… when trying to plot a film masterpiece, we generally forgive one mistake because the overall experience is enjoyable – and that’s the case with “Double Indemnity.”

Modern viewers might find some clunkiness to the old-fashioned staging, particularly of the romance between Neff and Phyllis. And although the film can be enjoyed from numerous angles, and for its many life lessons, it should be noted that it seeks to master noir tropes rather than redefine or undercut them to find new meanings. (Everything comes in its time. Wilder would pull off such a trick with “Sunset Boulevard” six years later.)

But the acting – particularly by voiceover-narrating MacMurray and femme fatale Stanwyck — is what the noir style calls for. Boxes are likewise checked for pouring rain and shadows cast by venetian blinds. And Wilder pours tragedy over a rail-straight line of concluding scenes, giving an early hint of his skill as a closer.

“Double Indemnity” leaves us with harsh, sobering and (because we generally like Neff) sad lessons: Don’t believe in easy money, and be careful who you trust. Live a moral and conservative life; don’t throw it away on a big shot. If you can murder your way to easy happiness, “Double Indemnity” is too straight-and-narrow of a noir to advocate that path. Maybe it’s not surprising, but it is admirable, both as a grounded fable and as a movie.

IMDb Top 250 trivia

- “Double Indemnity” ranks No. 103 on the list with an 8.3 rating, making it the fourth-highest rated Wilder film, behind “Sunset Boulevard,” “Witness for the Prosecution” and “The Apartment.” “Sunset Boulevard” is also the only film noir that ranks higher.

- It’s the only 1944 film on the list.

- Two other famous Cain adaptations don’t quite crack the list: “Mildred Pierce” (7.9) and “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (7.4).

- Chandler’s other famous films likewise fall a bit short, including “The Big Sleep” (7.9) and “Strangers on a Train” (7.9).

Wilder Wednesdays looks at the catalog of legendary writer-director Billy Wilder.