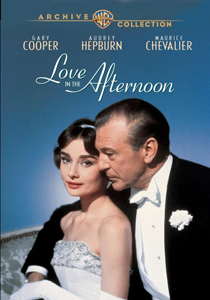

“Love in the Afternoon” (1957) is one of the most infamous May-December romance films, largely due to the cover art. Gary Cooper is actually two years younger than Humphrey Bogart, Audrey Hepburn’s eventual love interest in “Sabrina” (1954). But on the DVD cover, it looks like a grandfather sending his granddaughter off to her junior prom, so “Love” is the more notorious entry.

If modern virtue signalers watch the film itself, they’d be sweating it out, though. Sheltered French girl Ariane (Hepburn, 28, but looking younger) actually pursues American industrialist playboy Frank (Cooper, 56, but looking older).

If the actors’ ages match the characters’, they overshoot the “half your age plus seven” rule by seven years. But there are no issues of consent or coercion; he’s intrigued but not manipulative or forceful. One might argue that Frank should see through Ariane for acting more worldly than she is – but the whole point is that she’s entirely convincing.

“Love in the Afternoon” (1957)

Director: Billy Wilder

Writers: Billy Wilder, I.A.L. Diamond (screenplay); Claude Anet (novel)

Stars: Gary Cooper, Audrey Hepburn, Maurice Chevalier

Inauspicious first collaboration

This first collaboration between Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond continues Diamond’s run of exploring various angles of love. They’d do much better on the robust “The Apartment” (1960), one of the best rom-drams ever made. The premise is good here, too, but things go bad in the margins.

Frank believes in trysts with no attachments; Ariane believes in long-term love. His approach is based on logic, hers is based on storybooks. Also worth exploring is how a first love hits harder than future loves. It’s a common trope in TV shows, often with the naïve girl being loved and left by the guy who’s been around the block (Buffy and Angel), but sometimes the gender stereotypes are switched (Pacey and his teacher; Dawson and Eve). The writers raise these issues but don’t dig into them.

Diamond and Wilder tap into that oddity later raised by “American Pie’s” Rule of Three, wherein women desire romantically and sexually experienced men but men do not want experienced women. But that movie is 42 years in the future, so Ariane thinks she’ll impress Frank by listing the 19 men she’s been with. (I guess it’s a Rule of 19 for Ariane, whose only hangouts are the music conservatory and the apartment she shares with her dad. The “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” girl would be her bizarro twin.)

Instead, it aggravates Frank. But rather inexplicably, he’s more drawn to her. “Love” doesn’t really know why (except inasmuch as the answer to why people love each other is “love”). Or maybe it doesn’t care; it just wants to be goofy fun, running the main gag so far that a string quartet follows the couple on a river rowboat excursion.

Similar to another Wilder-Diamond misfire, “The Fortune Cookie” (1966), viewers know the beats but we must wait for the characters to get to them. In a 130-minute movie, it’s a long wait. “Love in the Afternoon” needs a witty pace and wacky set pieces, and it doesn’t have them.

More malaise than delight

Instead, it settles for extended sight gags. Ariane’s cello sticks out of the sunroof of her fellow musician’s tiny car. Frank hires out that group of string musicians for all his private engagements with regular paramours in Paris.

We seem to be building toward a gag where Ariane’s detective father Claude (Maurice Chevalier, the film’s best actor, finding a lightly absurdist vibe) can’t figure out it’s his own daughter who is seeing Frank (such a notorious playboy that Claude maintains a thick file). However, Claude is an entirely competent detective so he simply puts the pieces together once he has them.

While it seems “Love” might go screwball in the early going – with a good bit where a client (John McGiver) groans at each of Claude’s findings about his cheating wife — that’s not how it turns out. But it’s not a believable romance, either. Even though I’m fine with Ariane pursuing her heart’s content, I never believe what I’m seeing. Maybe it’s the age difference; it’s certainly a chemistry difference.

But beyond that, the script isn’t clever enough. Yes, Hepburn is better in “Sabrina” and Cooper is much better in “Ball of Fire” (1941), but those are vastly deeper screenplays. “Love” is all about relationships: Beyond their own relationship, Ariane and Frank only discuss their previous conquests (fictional in her case). We never see them bond over common interests or get awkward over uncommon interests. Although it’s a small film, it ironically lacks those important little moments.

Wispy vignettes about the nature of love are all well and good, but “Love” loses its wispiness. While a certain charm remains thanks to two movie stars and a great veteran actor, the film becomes more technical – and cliched, once we get to the train platform — than heartfelt. Instead of finding Ariane’s ideal of love, “Love in the Afternoon” accidentally finds Frank’s ideal of cynicism, even if the blunt fact of what we see on screen says otherwise.

Wilder Wednesdays looks at the catalog of legendary writer-director Billy Wilder.