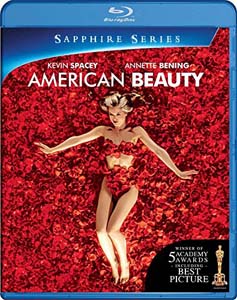

“American Beauty” (1999) shoulders the weight of being the chosen representative as the best movie of the best year in cinema history. It won the most Oscars (five), including Best Picture, and had the most nominations (eight). Although it has faced light backlash, it remains a timeless yet envelope-pushing message piece and artistic work, enhanced by a tinge of mystery from the question – sparked by Kevin Spacey’s opening narration — of “How does Lester die?”

It grows out of two movies from earlier that year, “Office Space” and “American Pie” (not that there was any cross-pollination, as all were made concurrently) along with the hot topic tackled by all edgy TV shows of the time: the rise of openly gay people in the population. But it is more dramatic. The two aforementioned films are among the best comedies of all time, just not as deeply felt as “American Beauty,” which admittedly isn’t as funny.

But it’s very funny when it wants to be. I particularly feast on Spacey’s not-missing-a-beat delivery of “Pass the asparagus” as Lester Burnham caps an explanation to wife Carolyn (Annette Bening) and daughter Jane (Thora Birch): He did not lose his job. He quit. And he brilliantly blackmailed his boss out of $60K.

“American Beauty” (1999)

Director: Sam Mendes

Writer: Alan Ball

Stars: Kevin Spacey, Annette Bening, Thora Birch

It’s a beautiful day in suburbia

That’s the “Office Space” riff; meanwhile, the teens play out a less-overt “American Pie”-esque sex obsession. This also illustrates the core theme: The characters who embrace their true natures are happy, and those who do not are miserable (and they also make their family members miserable). Jane’s friend Angela (Mena Suvari) is, in appearance, a sexpot. And she brags about her supposed exploits to Jane to the point where Jane is legitimately worried that Angela will seduce her dad.

But Angela is only happy once she tells Lester she is inexperienced at sex. She feels great once that’s off her chest. And Lester is a pretty good person to tell (in the world of this film, which gets so gradually and gorgeously messed up that cultural norms cease to matter), since he has learned the lesson of following his own bliss in the leading days and weeks.

Meanwhile, the normies have miserable lives. They’re represented by the Burnhams’ neighbor, Colonel Fitts (Chris Cooper), and Carolyn, both of whom are the definition of repressed. Fitts’ hatred of gay people is so 20th century, but the passing of time hasn’t hurt the drama of the final-act revelations. In fact, society’s rather rapid acceptance of gays makes Fitts’ storyline more tragic.

“American Beauty’s” artistry shines across the board, as writer Alan Ball and director Sam Mendes polish what was originally a riff on a dark-side-of-suburbia tabloid story into a meditation on how common it is for people to be two-faced – and how that makes them miserable. And also about how difficult it can be to break free of it.

We focus on Lester’s journey, and in parallel plots follow the struggles of others, but there’s also the third type of character: the foil. Ricky (Wes Bentley, barely too young to get Adam Scott’s career track) has already figured out how to be himself (a successful pot dealer and dedicated videographer). He hides it from his dad only as a survival mechanism. (Interestingly, he doesn’t hide it all that cleverly. At one point, he says his dad’s “denial” is the main reason he hasn’t been found out.)

Jane vs. Enid

Jane is also a foil; she has always been herself. But not by conscious choice, more so by confused flailing. Crucially, Ricky teaches her it’s OK to be true to herself. At that point, she sees her boob-job savings of $3K as something that could go toward worthwhile pursuits.

It’s impossible to not think of “Ghost World” (2001) when watching Birch here; the difference between Jane and Enid is a matter of degree, and of the characters’ tendency to see the bright side or the dark side of a given situation. Jane finds acceptance of her weirdness via the boy who conveniently lives next door, while Enid looks all over town and never finds acceptance. But to throw her a bone, Enid is asked to be flexible (and she fails), whereas Jane does not face that challenge.

Being lighter in its comedy beats but darker in message, “Ghost World” finds Enid unable to navigate that conformity-originality balance. A sympathetic reading is that Enid is punished for not conforming; by contrast, “American Beauty” punishes those who do conform. Along those same lines, the conformers of “American Beauty” (Fitts, Carolyn, and the pre-breakthrough Angela) hurt those around them, whereas in “Ghost World,” the non-conformer, Enid, hurts those around her.

Both movies feel “correct” internally, despite having opposite messages. In terms of character analysis, I think this is because Lester’s rejection of acting grown-up is a spark toward him finding balance between the two extremes. (Angela, by her presence, encourages him to work out, and Ricky’s quitting of his catering job inspires Lester to quit his advertising job.) Enid of “Ghost World” never achieves that balance.

More broadly, “Ghost World” is realistic and “American Beauty” is a fantasy. In 1999 and today, I’ve vaguely felt that the most forced part of “American Beauty” is Ricky’s – and then Lester’s – monolog about all the beauty in the world. Granted, any shortage of proof for that statement is papered over by the beauty of the movie itself, which remains a fine leading representative of an amazing artistic year.

IMDb Top 250 trivia

- “American Beauty” (No. 82, 8.3) ranks fourth on the list among 1999 films. Above it are “Fight Club” (No. 13, 8.8), “The Matrix” (No. 16, 8.7) and “The Green Mile” (No. 25, 8.6).

- Among worldwide critics, though, “American Beauty” holds less favor, as it does not appear in the BFI top 250. “The Matrix” is the highest-rated 1999 American film, at No. 122.

- Mendes cracked the list again with 2019’s “1917” (No. 123, 8.2). Ball earned a spot in TV’s top 250 by creating “Six Feet Under” (2001-05) (No. 90, 8.7).