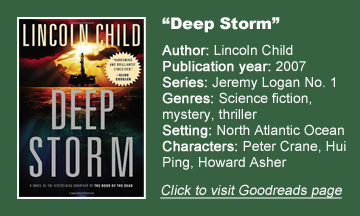

In “Deep Storm” (2007), Lincoln Child dives into some of the biggest science fiction ideas of his career without letting the story become untethered. While this, his third solo novel, ultimately hews closely enough to James Cameron’s film masterpiece “The Abyss” (1989) that I can’t say it’s entirely original, Child’s structure is masterful. He builds mysteries atop one another from the first page to the last, and each one plants a fresh hook.

A lot to think about

“Deep Storm” is propulsive not merely in the sense that there’s always something happening, but also — even neater — in the sense that a reader is always thinking about what’s happening. I’ll spoil the first revelation, since there are a dozen more after it: An oil rig in the North Atlantic, drilling deeper than ever before, believes it has discovered the lost city of Atlantis.

Child and Douglas Preston often take us to unusual parts of the Earth, but “Deep Storm” is hard to top because it goes beyond the limits of what’s technologically possible – but it might be someday.

In its secret archaeological dig, the U.S. government – having leased the platform from the oil company at a hefty rate – positions the titular facility on the ocean floor. Deep Storm itself couldn’t withstand the pressure at that depth, but around it is a dome that holds back the water. A system of tubed spokes let water flow through, relaxing the pressure somewhat.

Eerie underwater abode

As such, we get a decidedly eerie bubble where the ocean is kept at bay. Child takes advantage of this in the biggest thriller sequence, where main character Dr. Peter Crane and computer scientist Hui Ping have to climb the rungs on the side of the facility, trying to survive the cold, dangerous sprays of water, and the possibility of slipping and falling to their deaths.

Never one to keep facilities spartan in nature, Child describes Deep Storm’s interior as a fully functioning city, complete with a movie theater, libraries, dining halls, coffee shops and everything the scientists need for studying the fruits of the dig. The military is also very present, but it’s mostly on the secretive lower floors, beyond a heavily guarded barrier.

Crane – along with two fellow doctors — is initially wrapped up in a medical mystery on the upper floors; many people are acting strangely, something that vaguely calls to mind Michael Crichton’s “Sphere.” But that eventually morphs into multiple related brain-teasers in the realms of mathematics and computer programming.

An eerie quality hangs over everything since Deep Storm is such a strange environment, and Child adds to this with his talk about layers of the Earth’s crust, of which little is known for sure after the surface layer. I was familiar with the old saw about how we know less about the ocean than outer space, but I didn’t realize the layers of the solid part of Earth remain such big unknowns.

Sneaky character building

“Deep Storm” sneakily serves up lots of good characters considering that’s not Child’s focus. I love how the author builds Crane’s relationship with Hui so it can be read as a budding romance but it doesn’t have to be.

On the military side, Korolis is one of those standard P&C authority figures who thinks he knows everything – and we know he’s entirely on the wrong track – so it’s fun to follow an unlikable person down the wrong path.

Spartan represents the gray area of the military (he might or might not have the flexibility to do the right thing), while Asher – the scientist who brings Crane on board – has an infectious zest for solving the riddles of the universe. An old man named Flyte, who throws out pointed phrases from ancient literature, adds further intrigue.

“Deep Storm” is listed as No. 1 in the Jeremy Logan series, but Logan plays only a minor role. It’s an important one, though, as Asher sends him to various remote monasteries around the globe to dig into their libraries for accounts about Atlantis.

There’s something about libraries in remote places – preferably with brick walls that don’t entirely keep out the cold, lit only by candlelight – that makes a reader grasp the historical weight of collected knowledge. Because of his unique job as a historian specializing in weirdness, the notion of future Logan novels is appealing, but for now he’s a functionary for someone else’s plot.

After reading through all these mysteries and revelations, it comes down to the question of whether the solution is satisfying, if everything holds together in retrospect. It is, and it does. Child pushes the possibilities of underwater habitats and drilling technology, and a wild SF idea is at “Deep Storm’s” core.

But Child keeps things on enough of a human level that we can’t help but follow Crane and company in thinking about the universe, math as a universal language, aliens and the nature of God from fresh angles.