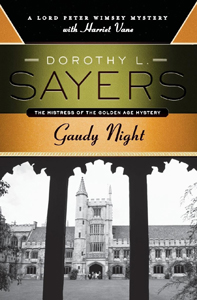

Dorothy Sayers marks the occasion of her 10th Lord Peter Wimsey bow, “Gaudy Night” (1935), with a novel that’s messy, socially fascinating, narratively ambitious, unwieldy, and a candidate for the best mix of detective fiction with romance.

It’s also much more of a Harriet Vane novel than a Wimsey novel. While he does most of the talking when he’s on the page, and while we learn a lot about him (via Harriet taking him more seriously as a prospective partner), this is very much Harriet’s adventure.

There’s the slimmest of chances J.K. Rowling was inspired by “Gaudy Night” when writing her “Harry Potter” novels. The setting is Shrewsbury College, the all-female branch of Oxford University, where Harriet partakes in the Gaudy Night (essentially Homecoming) festivities about a decade after her graduation. She sticks around at the invitation of the dean because poison-pen letters are circulating. Harriet is a famous mystery author, and so it goes that people assume she can solve a real-world case.

“Gaudy Night” (1935)

Author: Dorothy L. Sayers

Genre: Mystery

Series: Lord Peter Wimsey No. 10 (third with Harriet Vane)

Setting: 1935, Oxford University

Shrewsbury might not be as architecturally fascinating as Hogwarts, but there’s still a moody vibe as acts of vandalism by a cloaked figure happen after dark. Mysterious lights are on, curtains are drawn, alibis are shaky. Harriet, the group’s reluctant leader, and various teachers gather in the common room and begin referring to the villain as The Poltergeist.

“Gaudy Night” is an outstanding character piece for Harriet, as we understand why she’s reluctant to marry Peter (a running gag of their previous team-up, “Have His Carcase,” finds him asking for her hand in marriage at regular intervals) despite quite liking him. A couple other characters pop, too; interestingly they are both young men despite 90 percent of the cast being female: a good-hearted but clownish student named Pomfret and Peter’s unfocused ladies’-man nephew Viscount Saint-George.

School ties

The book really could’ve used a dramatis personae (check out the one on Wikipedia while being careful to not peek at whodunit in the synopsis). I had no hope of separating the dean from the warden from the dozen teachers. Outside of Harriet, the best piece of character-building for a female comes in the final pages as we learn the full motivations for various actions.

Although I scoff at the notion that Sayers is “widely considered the greatest mystery novelist of the Golden Age” on newer printings (now there’s some indefensible research), I do admit that her ambition here outstrips anything Agatha Christie tried. Christie’s Mary Westmacott novels eschew mystery, and her mysteries don’t go this deep into social commentary; see her comparatively thin poison-pen mystery “The Moving Finger.”

Sayers doesn’t totally succeed, but it’s admirable that she wants “Gaudy Night” to be both a mystery and a study of 1935 British society at a time when, yes, the traditional path of family woman is still open, but academic careers are newly in the picture. This is before the “women can have it all” movement, and Sayers makes women’s binary choice into something palpably, permanently filled with tension.

She doesn’t pull it off with the smoothest of writing start to finish. It’s a decidedly decompressed novel, like a car that always makes it up the steep hill, but just barely. The opening chapter is incredibly long, as we’re introduced to (and Harriet is reacquainted with) the Shrewsbury faculty, but even there the school setting makes more of an impact than any personalities.

Sayers aims for the notion that some women are wives, and are either happy or jealous of the academicians; and some women are scholars, and are either happy or jealous of those starting families. Others are at every interval in between. Generally, the majority of 1935 women at least feel the anxiety of wondering if they made the correct of the two binary choices.

A pivotal time

While I wished feelings and traits would’ve been more firmly attached to specific teachers and students, the author’s interest in the “women’s societal role” conflict is a valuable historic snapshot, and actually universal across time and gender. Men and women deal with work-life balance today.

Indeed, the expansion of women’s roles also led to the expansion of men’s roles (in that men can be househusbands), although for the purposes of “Gaudy Night,” the immediate concern is that men are losing jobs to women new to the workforce.

Inasmuch as this is a novel about chaos in a women’s college caused by a villain angry about changing societal roles, one might assume Sayers longs for the clarity of working men and homemaking wives. But I don’t get that impression. I imagine she knows chaos makes for a great mystery backdrop. And while change always leads to upheaval, it doesn’t mean change is wrong.

Indeed, the book’s philosophical aspect expands to other moral conundrums. For instance: Should you do the right thing even if it ruins someone’s life? And conversely, should you let someone get away with a minor transgression because you know the penalty will be out of proportion with the crime?

There’s a lot of good stuff in the 23 long chapters of “Gaudy Night.” It will take you an unnecessarily long time to get through it, and the literal weight of the tome is too much for the philosophical weight of the tome. But it’s still worth reading, even if you come only for the mystery or only for the Vane-Wimsey relationship. Those who like both will have the best time.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.