A century ago, Alfred Hitchcock quietly (indeed, soundlessly) started his career with throwaway rom-dram “The Pleasure Garden.” Fifty-two years and exactly 52 films later, he was the bona fide Master of Suspense and a strong candidate for the status of greatest director of all time, and his work is much more likely to be carefully preserved than thrown away. (The tidy math is made possible because a 53rd film, 1926’s “The Mountain Eagle,” is lost. Always one to look ahead to his next project, Hitch never seemed too bothered by it.)

By the Forties and Fifties, when the Brit had moved to America, he teamed with stars like Ingrid Bergman, Cary Grant, James Stewart and Grace Kelly to make some of the greatest films of all time. But arguably, he didn’t even need the star power, as he became the first director famous for his look and personality. People went to films because he was the director, and watched his TV show because he hosted it.

Not that Hitchcock’s work took a back seat to his celebrity; even his last film, 1976’s “Family Plot,” helmed at age 76, is intricate and entertaining. Here are my rankings of the master’s 52 films. Nobody’s perfect, so we start with some bad ones, but it gets better fast. (Click on each title for a full review.)

52. “Juno and the Paycock” (1930)

Hitchcock’s first full talkie is an exercise in misery both intended and unintended. Intended: A poor Irish family scrapes by; the spouses don’t get along, the war-veteran son is depressed, and the daughter is pregnant out of wedlock (the worst mistake a young woman could make). Unintended: The film lacks dynamism, clever laughs and nuanced tragedy. Mostly confined to a drab apartment with the wider conflict (the Irish civil war) being inaccessible to modern viewers, “Juno” was never great, and it has aged horribly.

51. “Mr. & Mrs. Smith” (1941)

There’s nothing harder to watch than an unfunny comedy, and that’s what we have here as two unlikeable spouses (Carole Lombard and Robert Montgomery) find themselves unmarried by a quirk of the law. Montgomery, when finally deciding he wants Lombard back, then must court her. The funny lines (one good one: Lombard’s dress has “shrunk” since she last wore it) are too spaced out, prospective suitor Gene Raymond is cruelly the butt of jokes, and writer Norman Krasna has no clever set pieces up his sleeve.

50. “The Farmer’s Wife” (1928, silent)

This is the earliest example of Hitchcock’s painfully unfunny comedies. Though it can’t sustain even a quarter of the 111 minutes, the film’s premise is actually not that bad: A widower (Jameson Thomas) bungles courtships with four wife candidates, oblivious that his sweet young maid (Lillian Hall-Davis) loves him. Early Hitch regular Gordon Harker brings physical gags (involving pants that won’t stay up) but Hitch and his editor have no sense of comedic rhythm.

49. “Jamaica Inn” (1939)

I find historical dramas set in dreary times unappealing to begin with, but Hitch’s first of three adaptations of Daphne du Maurier stories doubles down on the dreariness. This story of brazenly corrupt coastal-town politics is the last film of his British period, and some suggest Hitchcock had mentally already left for big-budget Hollywood. Even though “Jamaica” has outdoor shipwreck scenes, it’s stodgy and depressing. Charles Laughton steals the show, but in this case that phrase is not meant positively.

48. “The Birds” (1963)

It’s in the top 10 of most lists, and I heartily disagree. The special effects were groundbreaking but now look like composited fake birds shot against a yellow screen. The acting is weak, and the most interesting member of a love triangle (Suzanne Pleshette) is dispatched while we focus on Rod Taylor and Hitch’s “Vertigo”-esque obsession, Tippi Hedren. The story doesn’t end, and the reason is not artistic: They don’t have the budget nor the confidence to shoot a storyboarded final battle against the birds. Coming from a du Maurier short story, the film is historically important for popularizing real-animal-based horror, so at least it begat “Jaws.”

47. “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934)

Although Hitch’s first crack at this story has plenty of defenders – and the cast features Peter Lorre and a young Nova Pilbeam – the story and characters (other than Lorre’s garrulously scary villain) are hard to keep straight. Hitch takes a key step into bombastic grand-finale showmanship with the Royal Albert Hall concert, but there’s a reason why he remade “Too Much” two decades later: He knew it could be done better.

46. “Under Capricorn” (1949)

The Master of Suspense is not a master of period pieces or pacing. While it’s not hard to look at the colorful costumes and matte backgrounds of rugged 19th century Australia, nor at Ingrid Bergman as a drunk who two rival men hope to nurse back to health, the show-offy long takes are hard to watch. The movie manages to be long without delving into the true history of ex-convicts who carved out new lives for themselves. Star Joseph Cotten called this “Under Corny Crap,” and it’s hard to argue.

45. “Lifeboat” (1944)

Hitchcock had been making more outdoorsy films around this time, but even though this one is set on the high seas, it is claustrophobic, obviously a boat in a tank against a rear-projection ocean. The performances are sharp, including scenery chewer Tallulah Bankhead as an oddly entitled journalist, but “Lifeboat” suffers today from a heavy-handed “Nazis are evil” theme. Interestingly, in its time it was criticized for being sympathetic to Nazis by showing the German character’s strength.

44. “The Skin Game” (1931)

Like “Juno and the Paycock,” this is a work-for-hire filmed stage play. But it’s decidedly more watchable, featuring a thought-provoking conflict of developers versus landed gentry (past versus present, status quo versus advancement). The out-of-court maneuverings are stuck in their time, featuring a social controversy that wouldn’t be controversial today. But at least we can look at the glamorous Phyllis Konstam, who you might call a “Hitchcock Brunette.”

43. “Murder!” (1930)

A rarity in Hitchcock’s catalog: The story is stronger than the execution. Several scenes are overlong, dialog-heavy and nonsensical. The premise is excellent: Juror Sir John (Herbert Marshall) realizes in retrospect that he has given into the peer pressure of his 11 colleagues and condemned an innocent woman (Norah Baring). Though we want Sir John to set things right, the proceedings are clunky, likely because Hitchcock was never comfortable with mystery (where the audience doesn’t know what’s up) as compared to suspense (where the audience does know what’s up, and anxiously anticipates events).

42. “Number Seventeen” (1932)

In scholarly circles, this one is fascinating to discuss. Hitch is more ambitious than ever before when using models and fast edits on the climactic train sequence. But up till then, the story is so nonsensical (except in the broad sense of jewel thieves – and oblivious bystanders — meeting at house No. 17) that some critics have suggested it’s intended as a parody of overly complex heist movies. Though I’m not sure whether “Number Seventeen” is good or bad, it’s only 66 minutes long, and I appreciate that.

41. “Secret Agent” (1936)

Tonally all over the place, “Secret Agent” features spies (John Gielgud, Madeleine Carroll and Lorre) having a grand ole time before things get awkwardly, deadly serious. Ultimately, this muddy pre-World War I period piece, probably by accident, captures a depressing mood wherein the viewer knows a century of war lies ahead. The final train sequence, featuring composited shots of planes, is pretty good for the era, but Hitch would later surpass it many times.

40. “The Trouble with Harry” (1955)

With a droll style that connected in Britain and France more so than in the U.S. (although the action is set in Vermont), this is one of the master’s least suspenseful crime films. It deserves credit for being funnier than his other pure comedies, but it’s not a spoiler (as it’s revealed right off the bat) to say this is a one-gag movie about people trying to not be caught with Harry’s corpse. Look for a cute Shirley MacLaine in her first major role, and soak up the Technicolor of the autumn leaves to make the time ease by.

39. “Torn Curtain” (1966)

The least effective of Hitch’s late films finds hero scientist Paul Newman – in a miscast marriage with Julie Andrews – going behind the Iron Curtain to possibly end international conflicts, or possibly accelerate the end of the world. Even Hitch’s weaker films give us something to talk about: This one is notable for featuring a disturbingly realistic depiction of how hard it would be – even for a trained and determined person — to kill an enemy in hand-to-hand combat.

38. “The Ring” (1927, silent)

In his first film with significant comedy, Hitch crafts a romance story where it’s not at all clear whether champ Carl Brisson or challenger Ian Hunter will land ticket seller Hall-Davis. It’s more like a truncated primetime love triangle than a stereotypical rom-com with an obvious good guy and obvious bad guy. Big stretches of humor come from the uncouth physical antics of the trainer (Harker), and while “The Ring” is fairly painless to watch, “Rocky” it ain’t.

37. “Easy Virtue” (1928, silent)

Though it doesn’t quite earn Isabel Jeans’ biting final line to the tabloid photographers (“Go ahead and shoot; there’s nothing left to kill”), the commentary on celebrity is surprisingly current, in that Larita is “famous for being famous” like a Kardashian. It’s also very much of 1928 London. Divorce was not only nearly impossible if the other two parties (the husband and the government) rejected it, but even if you did succeed at getting one, you essentially were branded with a scarlet “D.”

36. “Waltzes from Vienna” (1934)

Although this is a work-for-hire piece, it’s noteworthy that Hitch for the first time embraces music as a cinematic tool. We hear “The Blue Danube” in its entirety in the climax of this biopic about 19th century composer Johann Strauss II (Esmond Knight) trying to please his overbearing father (Edmund Gwenn). The women in his life — Jessie Matthews and Fay Compton – are given full characterizations, and Matthews looks ethereal even in the grimy print that survives.

35. “The Lady Vanishes” (1938)

One of the 1930s films driven by the interplay of well-paired leads (Margaret Lockwood and Michael Redgrave), “Lady Vanishes” ranks lower for me than for most viewers. The concept is ingenious: Lockwood meets kindly titular lady Miss Froy (May Whitty), who then disappears. The plot thickens in a weird way: No other train passenger admits to knowing or even seeing Miss Froy. I had hoped for a clue-laden mystery, but that’s never the aim of Hitch or the writers, who bizarrely shift to into spy-game intrigue.

34. “Rich and Strange” (1931)

Also known as “East of Shanghai,” this early talkie’s strengths ironically lie in its visuals. A wordless opening sequence finds white-collar worker Henry Kendall struggling with the hustle and bustle, and when he and wife Joan Barry go on an international cruise, the scope opens further. It’s suspenseful fun to see the spouses attracted to other people (Percy Marmont and Betty Amann) on the cruise ship. As a luckless bachelorette, Elsie Randolph is among the first supporting-cast scene-stealers in a Hitchcock enterprise.

33. “Downhill” (1927, silent)

This is Hitch’s first pure psychological drama, chronicling Roddy (Ivor Novello), a young man who lets people walk all over him. Over three acts of being wronged in distinct ways (by a father, a girl and a job), Roddy descends into madness. In that third act, “Downhill” demonstrates that the sex-worker industry is not as enjoyable for the desperate Roddy as it is for the women in Hitch’s earlier film “The Pleasure Garden.” “Downhill” is not necessarily enjoyable, but it does make a statement.

32. “The Pleasure Garden” (1925, silent)

Hitchcock’s first film is technically competent out of the gate and avoids pitfalls of his weaker early works. At 1 hour in length, it doesn’t overstay its welcome. Stars Virginia Valli and Carmelita Geraghty, both imported from America, are easy to look at – although they confusingly look too similar – in a simple, sitcomish tale about how some people are genuine and others are phonies.

31. “Champagne” (1928, silent)

This is a throwaway effort, but that vibe serves it well as Hitch – helped tremendously by bubbly lead Betty Balfour – stumbles into whimsical lightness rather than off-target comedy. Adding to the lack of seriousness, Balfour’s character is simply The Girl, and her suitor is simply The Boy (Jean Bradin). Her father (Harker) aims to teach her a lesson to not be frivolous – by faking the removal of the family fortune – but she remains oblivious. She’s absurd, but maybe her approach to life has some merit.

30. “Foreign Correspondent” (1940)

The titular John Jones (Joel McCrea) is a journalist in the same way Indiana Jones is an archaeologist, but still it’s pleasant that the film imagines a Pollyanna world where good reportage shapes people’s views and politicians’ decisions. “Correspondent” is a rather oddball movie in that it’s a fictional account of how the U.S. enters World War II, made just before the real-world events. It was patriotic propaganda at the time, and now it’s a fascinating alternate history.

29. “Rope” (1948)

More experimental than great, “Rope” is notable for mimicking a stage play, using long-as-possible takes (10 minutes, in those days). But also Hitchcock moves the camera around uses neat tricks such as focusing on listeners instead of talkers. Among Leopold and Loeb riffs about killers who are in it for the challenge of getting away with it, “Scream” is the more successful film. But “Rope” does feature food for thought about how a killer might develop a sense of privilege, plus there’s darkly fun tension with people getting close to opening the trunk containing a corpse.

28. “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1956)

Hitch knew he could improve upon his 1934 version, so when he found a gap between new scripts on his desk, he remade it with old reliable James Stewart, and Doris Day as his wife. The latter brings singing chops, leading to the chart-topper “Whatever Will Be, Will Be.” Another old reliable, composer Bernard Herrmann, gets the literal spotlight, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in the grand finale at Royal Albert Hall. A rare location shoot (in Morocco) further makes this remake grander.

27. “Marnie” (1964)

Hitchcock enters his weird but interesting final stretch with a film that wouldn’t be made today. Unlike in “The Birds,” Hedren shows she can act, ironically (to those who know the Hitch-Hedren relationship) as a the titular woman traumatized by interactions with men. Being so suave, Sean Connery is probably the only actor who could play a man who blackmails Hedren’s thief into marrying him while still not being the narrative villain. The denouement is unavoidably bizarre. Give Connery’s Mark Rutland credit for honesty, though, in blatantly admitting he sees Marnie as an animal with whom he can do as he pleases.

26. “The Paradine Case” (1947)

In David O. Selznick’s only writing (as opposed to producing) collaboration with Hitch, we’re treated to luscious black and white cinematography. Striking femme fatale Alida Valli is the prime suspect in the poisoning of her rich husband; we can understand why lawyer Gregory Peck is taken with her, despite being married to Ann Todd. The movie visually emphasizes the cruelty of suffocatingly packed British courtrooms toward defendants, even when they are in the “innocent till proven guilty” stage. “Paradine” could’ve achieved greatness if it added a layer of clue-driven mystery.

25. “Stage Fright” (1950)

Hitchcock’s Fifties winning streak starts with a better version of “Murder!” Whitfield Cook’s screenplay makes a chaotic string of events coherent, as everyone is covering for someone else due to secret love. It includes humor in the margins (a rich woman not knowing her maid’s name), a ratcheting of tension in the final act, and an early use of recording equipment to secure a confession. The film is most famous (or infamous) for presenting a flashback to the audience dishonestly. It could’ve played more fair, but as time has gone by and unreliable narrators have become more common, it’s less offensive than it was at the time.

24. “Blackmail” (1929)

Hitchcock enters the sound era in a big way, though not by doing everything that today’s films can do; instead, this plays like a silent film with occasional sounds. Its strength lies in a suspenseful tale of a woman (beautiful Anny Ondra) killing a rapist in self-defense and trying to act innocent afterward. Also, we get the POV of the detective (John Longden) who loves her enough to cover it up. In addition to the controversy of self-defense killings, “Blackmail” also is timeless due to Hitch’s first showy conclusion, a chase that ends on a museum skylight.

23. “Sabotage” (1936)

This is a tight character piece about a wife (Sylvia Sidney) – concerned about raising her kid brother — stuck in a marriage with a dreary husband (Oscar Homolka) who also happens to be a Nazi saboteur. It’s most famous for the bomb-on-a-bus sequence Hitchcock later regretted. By having the bomb go off long before the narrative was resolved, he felt he killed the momentum. That’s somewhat true, but nonetheless “Sabotage” is a tidy suspenser.

22. “The 39 Steps” (1935)

If one film is a code key for Hitch’s whole catalog, it’s this one, featuring leads with crackling chemistry (Robert Donat and Carroll) in the story of an innocent man on the run and a woman who is stuck with him. (They are literally handcuffed together.) The pacing is so brisk and the narrative so twisty we don’t have time to be angry on Donat’s behalf; and besides, it’s light enough that we can presume a happy ending. The story is more just-plain-silly than delightfully silly, but I can understand “39 Steps’ ” staying power.

21. “Suspicion” (1941)

With Cary Grant in his first Hitchcock role and Joan Fontaine returning from “Rebecca,” there’s a lot to like here. The question of whether Grant’s likeable gadabout Johnnie, who talks Fontaine’s rich Lina into marrying him, is genuine or running a giant con makes for compelling viewing. The film is famously hurt by an awkward ending where Hitchcock was required to portray Grant as a good guy for the studio, but “Suspicion” is safely in the category of “worth seeing.”

20. “Young and Innocent” (1937)

I’m in the minority in liking this more than the extremely similar “39 Steps.” Giving it the edge is Pilbeam, one of those actresses the camera loves, and it’s refreshing that her character believes in the innocence of the man (Derrick De Marney) fairly quickly. Making it less murky than the spy-game convolutions of “Steps,” here we know the actual culprit, so “Young and Innocent” turns into a romping howcatchem – a format Hitch likes much better than whodunits.

19. “Topaz” (1969)

This ambitious and vibrant late-career entry finds statesman John Forsythe in a world-hopping romp where he’s on the razor’s edge of ending the Cold War. Hitch unleashes several thrilling set pieces (an attempt to infiltrate and escape a hotel housing the core of the enemy), and scenes of artistry (a key conversation plays silently behind glass) and dark beauty (red blood pools around a violet-dressed corpse). Unfortunately, he and screenwriter Samuel L. Taylor, despite their success on “Vertigo,” end the story with a whimper.

18. “The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog” (1927, silent)

A prototype for all Hitchcockian plots to follow, this silent film also continues the “Pleasure Garden” theme of how we shouldn’t make assumptions about people. The lodger (Novello) is thought to be the homicidal Avenger because he’s antisocial. This timeless film remains striking for making the suspect the main character. I’d like to note that although this is sometimes considered a Jack the Ripper story, it’s actually only inspired by that 19th century case; this one takes place in 1927.

17. “The Manxman” (1929, silent)

This remake of a lost 1916 film is about as emotionally honest as a love-triangle story can get. Best friends (poor Brisson and well-off Malcolm Keen) both have eyes for what appears to be the Isle of Man’s only girl (Ondra). Is the girl the key to happiness, or does defeating a friend in pursuit of the girl defeat the whole purpose? With more psychological depth than the similarly themed “The Ring,” this is Hitchcock’s richest silent film.

16. “To Catch a Thief” (1955)

A lighter yet delightful film among Hitch’s great Fifties run pairs Grant and Grace Kelly. Unlike in “Suspicion,” we know Grant’s John Robie truly is reformed from his cat burglar days and he’s not the thief the authorities aim to catch. Kelly’s Frances is more worried about whether she can pry John away from his other suitors, such as French friend Danielle (Brigitte Auber). It’s neat to see Hitchcock work around the censors to create a sensuous scene between the two movie-star leads, with fireworks outside the window representing their liaison.

15. “North by Northwest” (1959)

Though I find “NxNW” overrated (it’s in the top four of most rankings), its influence can’t be denied. This movie was a hit because people were thrilled to see a just-plain-fun movie, logic be damned. It paved the way for the “James Bond” and “Mission: Impossible” franchises, not to mention the Zucker Brothers’ absurdities. A core principle is that you don’t need to make sense of everyone’s actions, you just need to grasp the “good guy vs. bad guys” dichotomy. It’s most crisply illustrated when Grant’s Roger Thornhill is attacked by a biplane in the middle of nowhere (rather than the villains simply shooting him). Hitch’s notion was that it looked cooler. I can argue with some of what “NxNW” has wrought, but the film itself is indeed a fun – and funny — romp.

14. “Frenzy” (1972)

Hitch revels in the post-Hays Code freedom to make this giallo-esque dark comedy, switching POVs between the actual Necktie Strangler and the man being framed. The director goes more violent and more sexual than he had before, and it’s fascinating to think about whether this makes for a better or worse film. That’s up to each viewer, but if nothing else, these style points make it stand out from the pack. Regardless, Hitch retains his ability to weave between violence and pitch-black chuckles (“You’re not wearing your tie”).

13. “Family Plot” (1976)

After slowly establishing the fake supernatural con games of a couple (Bruce Dern and cute Barbara Harris), Hitchcock’s last movie eventually clicks into a brilliant interlocking plot. William Devane is also fun to watch as a smirking villain who fronts as a jewelry seller. Although every major player is a criminal, the screenplay by “North by Northwest’s” Ernest Lehman is such fun that we end up liking all of them for their absurdities. It leads to a boffo conclusion and a fourth-wall-breaking wink at the audience that puts a tidy bow on the master’s catalog.

12. “Saboteur” (1942)

The first of the American “innocent man on the run” stories – a.k.a. the “one that ends at the Statue of Liberty” — finds Robert Cummings as a John Q. Public framed by a shadowy cabal like a David Mamet screenplay has targeted him. The story gains a layer of foreboding as the American government was working its will over the populace during wartime, and manifest destiny scope (albeit in reverse) as Cummings travels from LA to NYC with the requisite reluctant gal (Priscilla Lane).

11. “Spellbound” (1945)

The first major film to explore psychoanalysis (an opening crawl flat-out explains what it is) – while also touching on newish issues like shell shock and women in the workplace – this is a fascinating mix of romance and intrigue. Composer Miklós Rózsa, who elevated some Billy Wilder films, provides an Old Hollywood backing for a rather adorable match of Bergman (in her Hitchcock debut, clinically learning about love) and Peck (battling a mysteriously dark past).

10. “I Confess” (1953)

The premise might be more instantly relatable to Catholics: A priest must maintain the seal of the Confessional for a murderer even when he himself is wrongly accused. Montgomery Clift gives such a sympathetic, subtle performance, though, that even secular viewers will like him. We root for him to do the right thing for himself but understand why he won’t. It’s rare that a great character study comes out of someone who has no flaws, but this is one. It’s also refreshing that the screenplay by George Tabori and William Archibald doesn’t require the police detectives to be idiots. They want the priest to explain why all the evidence points to him, but he simply won’t help them.

9. “Strangers on a Train” (1951)

This screenplay by Raymond Chandler by way of novelist Patricia Highsmith builds the chaos to come from a relatable foundation. The passenger (Robert Walker) next to Farley Granger is chatty, so he humors him out of politeness and mild curiosity. But Walker is more than a minor annoyance, he’s a psychotic schemer, and soon Granger is wrapped up in a plot to kill two people. He’s innocent, but he looks guilty. Hitchcock hits all the stops of moral grayness while delivering iconic moments such as a murder reflected in eyeglasses, one man at a tennis match who isn’t watching the ball, and an out-of-control carousel. Among later riffs on this influential film is one of Woody Allen’s best morality tales, “Match Point.”

8. “Notorious” (1946)

U.S. agent Grant must ask himself if his duty or his love comes first when he falls for Bergman, reluctantly sent undercover with Nazis. One of Hitch’s elite character pieces gains another layer with the villain played by Claude Rains, as we get a good picture of how being a Nazi does not protect you from Nazi atrocities. Famous for the innovative crane shot that zooms in on a key in Bergman’s hand – thus building up tension as to whether she’ll get caught with the key – “Notorious” features such a good plot that “Mission: Impossible II” flat-out copied it. Despite having no action scenes and letting the maguffin be nothing more, “Notorious” does it better.

7. “Shadow of a Doubt” (1943)

Hitchcock was crackling with Americana soon after his move to Hollywood; here he goes to the Rockwellian town of Santa Rosa, Calif., for the engrossingly tragic family fallout between teenage Charlie (Teresa Wright) and visiting Uncle Charlie (Cotten). Is he the great, world-savvy guy the family thinks he is, or is he the Merry Widow Killer? On first viewing, enjoy the intrigue; on subsequent viewings, enjoy the performances. Although it comes from a dehumanizing villain, Uncle Charlie’s monolog comparing rich widows to swine is hard to resist quoting.

6. “The Wrong Man” (1956)

Hitchcock made countless films about wrongly accused men, but this is his most sober entry, documenting the true story of Manny Balestrero (a bedraggled Henry Fonda), who goes through hell simply because he resembles a suspect. We also see how this affects his wife (Vera Miles). It’s interesting to note that censors could even interfere with true stories, as the wife’s mental-health problems are smoothed into a happy ending. Because the story is equally as crazy as Hitch’s purely fictional works, the director personally introduces the story (as he also did with his TV episodes) to set the real-world tone. We feel the suspense, but also a healthy outrage at the system.

5. “Rebecca” (1940)

Though things were contentious behind the scenes, Hitch’s second du Maurier adaptation ends up a perfect mix of producer Selznick’s Old Hollywood grandeur, driven by Franz Waxman’s score, and Hitchcockian touches of suspense. Fontaine was more of a presence than an actress – with the editor salvaging a performance – but quite a striking presence she is, as the young wife of Laurence Olivier. Suspense comes from the wife’s internal question of whether she wants to be at mist-shrouded Manderley — exacerbated by the iconically gaslighting Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson) – combined with the mysterious fate of first wife Rebecca, one of the most famous title characters who never appears on screen.

4. “Dial M for Murder” (1954)

Hitchcock builds suspense in a single apartment, and delivers that iconic 3D shot of Kelly desperately reaching for scrapbooking scissors to fend off an attacker. (The picture also plays fine in 2D, which is how 99 percent of viewers will see it.) But Frederick Knott’s screenplay, based on his own play, is the main reason I adore this film. It smoothly slides between whodunit, howdunit, how-frame-’em and howcatchem. John Williams’ Inspector Hubbard deliciously shifts from a generic police detective to a savvy one, inspiring the invention of TV’s “Columbo.” Oh, one more thing: Though it’s not mentioned as much as others, and though Hitch himself wasn’t big on it, this is among his perfect films.

3. “Rear Window” (1954)

One of Hitch’s most-studied films is about a specific kind of addictive voyeurism that translates to modern, curated social media. Jeff (Stewart), stuck at his own window with two broken legs, observes neighbors in the apartment units across the way through their windows. They can display what they want about their lives by leaving their curtains open, and he can make whatever conclusions he wants. Meanwhile, he neglects his own life, even though he has the world’s most beautiful woman (Kelly’s Lisa) waiting on him. Oh, and there’s a murder mystery, with creepiness that comes from what Jeff and Lisa imagine Thorwald (Raymond Burr) has done to his wife, based on scant clues. And there’s the lingering moral question: At what point does Thorwald’s life become any of their business?

2. “Psycho” (1960)

If there exists a person who has not absorbed the spoilers through the ether, “Psycho’s” twists would still work on them. But mostly it is now appreciated for its influence, such as lines around the block to see a pop-culture phenomenon, and the way it subverts a core storytelling convention (don’t switch the POV character midway) in order to heighten – rather than lessen – the impact. The slasher subgenre plants its roots here (along with the same year’s “Peeping Tom”). Although Hitch eschewed franchise storytelling, “Psycho” exploded into a franchise once the copyright holders were clear of his death and wrath: three film sequels, three sequels in Robert Bloch’s book series, an experimental shot-for-shot remake (which further illustrates the master’s touch on the original), and one of the best TV series of the 2010s (“Bates Motel”).

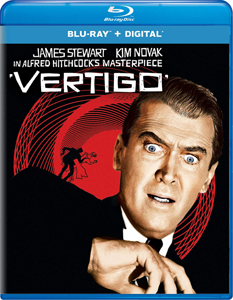

1. “Vertigo” (1958)

Rightly ranked by the British Film Institute as one of the greatest movies ever made (No. 1 for a while, and currently No. 2), “Vertigo” marks a payoff of Hitch’s careful planning and the kismet that touches elite films. Among the artistry and symbolism that inspire countless professional and armchair analyses and theories, “Vertigo” is at heart a warning about obsession, uneasily couched in a glorification of obsession. Stewart’s Scottie loves Kim Novak’s character in the purest way (love at first sight) but also the most dangerous: He knows so little about her that she might not even be who she says she is. The villain’s plot seems so complex it can’t possibly make sense, but it ultimately does, even if it leaves open the question of why the hotelier is covering for Judy. Because the film is so artful overall, even the one possible plot hole becomes ripe for analysis.